A capability describes what a business does and refers to a particular ability or capacity that a business possesses to achieve a specific purpose or outcome.. Capabilities can be decomposed into more granular or specific Capabilities. Capabilities should have a strict hierarchy, i.e., a Capability has one and only one parent Capability.

Capability management is the approach to the management of an organization, typically a business organization or firm, based on the "theory of the firm" as a collection of capabilities that may be exercised to earn revenues in the marketplace and compete with other firms in the industry. Capability management seeks to manage the stock of capabilities within the firm to ensure its position in the industry and its ongoing profitability and survival.

Prior to the emergence of capability management, the dominant theory explaining the existence and competitive position of firms, based on Ricardian economics, was the resource-based view of the firm (RBVF). The fundamental thesis of this theory is that firms derive their profitability from their control of resources – and are in competition to secure control of resources. Perhaps the best-known exposition of the Resource-based View of the Firm is that of one of its key originators: economist Edith Penrose.[1]

"Capability management" may be regarded as both an extension and an alternative to the RBVF, which asserts that it is not control over physical resources that is the basis for firm profitability but that "Companies, like individuals, compete on the basis of their ability to create and utilize knowledge;...".[2] In short, firms compete not on the basis of control of resources but on the basis of superior Know-How. This Know-How is embedded in the capabilities of the firm—its abilities to do things that are considered valuable (in and by the market).

Types of business capability

Dorothy Leonard defines three types of business capability that a firm might possess: Core Capabilities, Enabling Capabilities and Supplemental Capabilities.[3]

Core Capabilities are defined as those "built up over time", that "cannot be easily imitated" and therefore "constitute a competitive advantage for a firm". They are distinct from the other types of capability and sufficiently superior to similar capabilities in competitor organizations to provide a "sustainable competitive advantage". It is implied that such core capabilities are the product of sustained, long organizational learning.

Supplemental Capabilities are defined as those that "add value to core capabilities but that could be imitated".

Enabling Capabilities are defined as those that "are necessary but not sufficient in themselves to competitively distinguish a company." In other words, enabling capabilities are those which a firm has to do, in support of its normal operations and core capabilities, but which are not themselves core capabilities (because they could be imitated, developed quickly or would not be very different from competitors' capabilities). Enabling capabilities are distinguished from supplemental capabilities in that they are required, but do not necessarily add value to core capabilities.

A business capability is what a company needs to do to execute its business strategy (e.g., enable e-payments, tailor solutions at point of sale, demonstrate product concepts with customers, combine elastic and non-elastic materials side by side, etc.).

Another way to think about a capability is that it is an assembly of people, process and technology for a specific purpose.[4]

Capability Management is the active management, over time, of the portfolio of capabilities in a firm – their development and depreciation in conscious response to changes in the business environment.

Capability management is an approach that uses the organization's customer value proposition to establish performance goals for capabilities based on value contribution. It helps drive out inefficiencies in capabilities that contribute low customer impact and focus efficiencies in areas with high financial leverage; while preserving or investing in capabilities for growth.

Distinctive capabilities

Oxford economist John Kay defines Distinctive Capabilities as those capabilities a firm has which other firms cannot replicate even after they realize what the benefits are that owning the capability confers. These distinctive capabilities are the source of superior performance of successful firms. Kay's Distinctive Capabilities may be identified with Leonard's inimitable and hard-won "Core Capabilities". However, Kay goes further in arguing that in order for a capability to be truly distinctive and the basis for competitive advantage it must meet two further criteria: sustainability and appropriability.

Sustainability refers to the firm maintaining the distinctiveness and superiority of the capability relative to other firms despite their efforts to imitate or replicate it. One approach to sustainability is for the firm to develop the capability faster than the competitors through learning and innovation.

Appropriability refers to the firm securing the benefits of the capability – or the exercising of its capability – for itself as opposed to those benefits accruing to the firm's customers, its staff – management or employees, or its shareholders, regulators or other stakeholders. Intellectual Property Rights are one means for securing appropriability.

On the basis of analysis of empirical data regarding the performance of companies Kay argues that there are only a few types of distinctive capability that meet the additional criteria. Three are said to recur in the analysis: Innovation, Architecture and Reputation. These are briefly discussed below.

Capability or competency

In a 1990 edition of the Harvard Business Review, Gary Hamel and C.K.Prahalad published an article entitled "The Core Competence of the Corporation" which defined the notion of a "core competency". Core Competencies are identified by three criteria: 1) they are difficult for competitors to imitate 2) they make a substantial contribution to a number of the firm's products (or services) they give the firm access to several markets and 3) they make a substantial contribution to the perceived customer-value of the products (or services). The (superior) competitive position of the firm's products (or services) in its markets is thought to be the expression of the firm's competitive advantage. Hamel and Prahald go on to assert that core competencies are the result of "collective learning across the corporation".

Since that publication there has been active debate in the academic literature as to whether (the concept of) "core competencies" is the same notion as core capabilities. Several authors consider that the concepts are the same, the differences purely terminological, and use the terms interchangeably while others insist there is a substantive distinction. Given the similarities in their definitions it is a reasonable position to think they are the same. However, neither Leonard, nor Hamel and Prahalad (nor indeed Kay) were philosophically precise enough in their definitions and expositions of the concepts for the identity to be definitively established. One reasonable position is that "core competencies" are a view of "core capabilities" from a customers and products perspective while "core capabilities" are a view of "core competencies" from the perspective of knowledge and skills and staff and suppliers in firms. This may reflect the philosophical biases of their respective institutions.

Others, such as Max Boisot, take the view that competence or competency is some measure of the level of performance in a capability or that competence is a much narrower concept than capability. Hence a firm may have a high or low level of competence in a particular, notional, abstract capability. There is some evidence that general managers often fail to appreciate the subtlety of the definition of "core competencies" and over-estimate the degree of their firm's competence in common capabilities. Consequently, they over-identify "things the firm is good at" as core competencies – which falls foul of the distinctiveness criterion for a core capability (and/or the inimitability criterion of core competencies and core capabilities). Hence some things managers mistakenly identify as "core competencies" may be more properly considered as Enabling or Supplemental Capabilities.

When applying the concepts of "core competence" or "core capability" academics and practitioners should be clear and precise as to their intended semantics for these ambiguous terms.

Structure of a capability or dimensions of a core capability

Leonard analyzes the nature of a (business) capability and concludes that core capabilities "comprise at least four interdependent dimensions" (pp. 19) as follows:

- Physical technical systems – machinery, databases, software systems etc.

- Managerial systems – systems for the management of operations, including operation of technical systems

- Skills and Knowledge (systems) – systems for the maintenance of personal and team skills and knowledge

- Values and Norms – systems for the regulation of behaviours and objectives in organizations

Around this complex of systems that realize a core capability Leonard situates a loop "Capability-Creating Activities" that comprise "Shared Problem Solving" and encompass Present and Future and Internal and External Perspectives (see Leonard, 1995, chapter 3). This capability development loop, is considered a system of organizational learning (knowledge-creating and knowledge-diffusing activities) and comprises the following activities:

- Problem Solving (in the context of the PRESENT)

- Implementing and Integrating (in the INTERNAL context)

- Experimenting (in the context of the FUTURE)

- Importing Knowledge (from the EXTERNAL context)

These activities, however, do not form a simple cycle or sequence and may be conducted in any order and several "in parallel" around any particular capability. It is these knowledge-creating and knowledge-diffusing (or knowledge-acquiring and knowledge-sharing) activities that make the capability dynamic (change over time) in the Leonard model.

Clearly, Leonard takes a System-of-Systems perspective on organizational or business or enterprise capabilities – and this establishes the link to the notion of a Capability in Systems Engineering. Given that the Leonard model of a capability incorporates elements of skills and knowledge, and is adaptive and intelligent in the sense of importing knowledge from the external context, experimenting and problem-solving, while moving from present to future, it may be considered an ICASOS – an Intelligent Complex Adaptive System-of-Systems – model of an enterprise or firm. Note that the knowledge created and diffused in the Leonard model is organizational knowledge, not personal knowledge and is Know-How, not Know-That, that is often Tacit Knowledge.

According to Hadaya and Gagnon, in their book Business Architecture - The Missing Link in Strategy Formulation, Implementation and Execution, a business capability is an integrated set of resources designed to work together to achieve a particular result.[5] A capability is always made up of one or more business functions, business processes, organizational units, know-how assets, information assets and technology assets. ″For example, to have the capability to Fabricate Metal Parts, an organization must have the necessary machines (technology assets), the knowledge of how to operate them (know-how assets), the specific sequence of activities needed to fabricate the parts (process), the drawings of the parts to be fabricated (information assets), and the teams of people (organizational units) specializing in the various types of fabrication required to make the parts (business functions)″.[5] According to these authors, some capabilities also include one or more brands or natural resource deposits. Indeed, ″the Coca-Cola Company could not sell 1.9 billion servings a day in more than 200 countries were it not for the power of its brands″.[5] In turn, for a farmer to be able to Produce Vegetables, he must have not only the right business functions, business processes, organizational units, know-how assets, information assets and technology assets, but also a piece of land (natural resource deposit) on which to grow his vegetables. A business capability can also be made up of lower-level capabilities. For example, to have the capability to manufacture cars, an organization must have several lower-level capabilities, including the capability to manufacture engines and the capability to fabricate and assemble the bodywork of the cars.

The consideration of a portfolio of capabilities in an enterprise in the context of the PRESENT and FUTURE contexts, with the Importing of Knowledge from the EXTERNAL context and the Implementing and Integrating of Knowledge in the INTERNAL context, establishes the link to Enterprise Architecture. In Enterprise Architecture this knowledge and planning of present-to-future evolution is diffused through the medium of models shared and used throughout the enterprise.

Dynamic capabilities theory

The Leonard model of a Capability is a dynamic model at the micro-level; focused on the detailed mechanisms for development and change of individual capabilities. Building on the work of Hamel and Prahalad, and others David Teece and colleagues developed a macro-level theory of Dynamic capabilities and framework for their management. In this theory a (or perhaps the) "Dynamic Capability" is defined as "the firm's ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments."[6]

Building on earlier work from the 1960s, the central thesis of the Dynamic Capabilities theory is that "... the real key to a company's success or even to its future development lies in its ability to find or create a competence that is truly distinctive". In this literature the term "competence" is used in both the sense of degree of performance in some capability and as a low-level, short-term capability. Competence in the latter sense echoes the concepts from Hamel and Prahalad, but may also be identified with Leonard's Enabling and Supplemental Capabilities as well as the short-term Core Capabilities of a firm. The term "capabilities" is also used somewhat interchangeably with "competencies".

The competencies or low-level capabilities are regarded as assets or knowledge-resources of the enterprise, alongside physical assets and other resources that are difficult for competitor firms to acquire. In this sense Teece's Dynamic Capabilities Theory is a move back towards the Resource-Based View of the Firm, but with a broader notion of "Resources" that includes intangible knowledge-based and practice-based resources, not just tangible assets. In the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, "Resources" are firm-specific assets that are difficult for competitors to acquire or imitate, "Organizational Routines" (based on prior work of Nelson and Winter) or "Organizational Competences" are the low-level capabilities of the firm and "Core Competences" are taken from the Hamel and Prahalad concept. Citing Dorothy Leonard (or Leonard-Barton), Teece et al. define (higher-level) Dynamic Capabilities as the "ability to integrate, build and reconfigure" these tangible and intangible assets. "Dynamic Capabilities thus reflect an organizations ability to achieve new and innovative forms of competitive advantage given path dependencies and market positions."

"Path dependencies" refers to the history of development of organizational knowledge embedded in its capabilities, routines and technological assets – echoing the concept from Leonard, but on a macro-scale and explaining why competitive advantage takes time and persistence to build. The incorporation of "Routines" and path-dependent development of firms in the theory establishes the link to evolutionary theories of management and (business) strategy.

The Dynamic Capabilities Theory also refers to notions of coherence, congruence and complementary assets across the firms portfolio of assets, routines, competencies and capabilities. This has resonances with similar notions of coherence in System-of-Systems Engineering and in Enterprise Architecture.

Teece et al. also discuss Technological Assets, Structural Assets and Reputational Assets – echoing the three recurrent categories of Distinctive Capability identified by John Kay – Innovation, Architecture and Reputation. The discussion of technological assets and technology-based competences establishes the link to Technology Management and Technology Strategy. Teece et al. also discuss organizational structure, market/industry structure, organizational boundaries, notions of co-specialization in assets, cross-firm integration and the trade-offs between hierarchical management control and a nexus of contracts. This presages notions of the "Virtual Enterprise" or "Extended Enterprise" and establishes the link to Enterprise Architecture.

It can be seen therefore that Dynamic Capabilities Theory is a highly integrative theory of the firm that links a wide range of fields including Business Strategy, Strategic Management, Knowledge Management, Technology Management, Technology Strategy, Systems Thinking, Enterprise Architecture or Enterprise Engineering and others.

From the perspective of Dynamic Capabilities Theory, Capability Management is the approach to management that focuses on the development of the portfolio of capabilities (resources, assets, routines, knowledge etc.) available to the firm, and the meta level capability of reconfiguring them and integrating them for market exploitation and competitive advantage.

Capability management in defence

Capability management in defence has a history dating back to the early years of the 21st Century. The UK Ministry of Defence adapted the existing DoDAF architecture framework to the procurement practices of what was then the MOD Procurement Executive, later Defence Equipment and Support, – in particular a Capability management approach to Defence procurement called "Through-Life Capability Management" (TLCM). The DoDAF was extended with additional 'Views' for capability planning and notions of capability configurations and capability increments. These views were standard ways to represent how the capabilities in some segment of the Defence Enterprise (such as the Army, Navy or Air Force) were expected to or planned to evolve over time, given investments by MOD and the UK Government. This was published in 2004 as the MOD Architecture Framework (MODAF) version 1.0. The current, and probably last, version of MODAF is 1.4. This will be the last version since MOD intends to migrate to the forthcoming new version of the NATO Architecture Framework, which incorporates much from MODAF, including the concepts and views of capability planning. The notion of capability in MODAF, however, is slightly different from the notion of capability in, for example, Dynamic Capabilities Theory.

In MODAF "Capability" refers to a military capability – an ability to produce military effects – or enabling or supporting capabilities. Nevertheless, the central thesis that politico-military conflicts or business competitions in markets are contests in which the organisation or enterprise with the superior capabilities wins holds. On this basis the same capability-based strategy and planning techniques are thought to be effective in both spheres.

The aim of "Through-Life Capability Management" (TLCM) was to promote in defence procurement a shift of perspective away from a focus on military equipment towards what was really required from UK Defence organizations: the capabilities, or abilities to produce effects in the world that enhance UK national security. The MOD considers that such capabilities are delivered by trans-organisation networks of operational units across the Defence Enterprise – and hence uses the terminology "Network Enabled Capability" (NEC). This is (a part of) MOD's interpretation of the concept of Network Centric Warfare which itself was a 1990s interpretation of a System-Of-Systems approach or perspective in the context of Defence.

The earlier cultural focus on equipment had led to over-specification, incoherent equipment purchases, unnecessary duplication, an over-emphasis on initial purchase costs, insufficient consideration of recurrent support and maintenance costs, project and programme delays and significant cost overruns that the UK Government could no longer tolerate. TLCM promoted a capability lifecycle perspective, that sought a balanced investment profile in time that would minimise whole-life costs, while efficiently producing effective, coherent and maximally cost-effective Defence capabilities over the medium term – and thereby ensuring maximum Value-for-Money for the UK taxpayer from Defence. TLCM was therefore central to the strategic planning of the evolution of the UK Defence Enterprise. While formally superseded, elements of TLCM live on in MOD's whole-systems, non-equipment-centric System-Of-Systems Approach, which was mandated in UK Defence Strategic Direction in 2013.

Capability management and strategic management

Capability management and enterprise architecture

Capability-based planning had long been entrenched in the defense realm in the US, UK, Australia, and Canada before it was adopted within Version 9 of The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF).[7]

Capability Management has in recent years become a popular sub-discipline or method of Enterprise Architecture. Enterprise Architecture seeks to build a rigorous model of an enterprise that identifies its component parts and their relationships for the purpose of planning the evolution of the enterprise. A Capability Management perspective – such as Leonard's model or Teece's Dynamic Capabilities Theory – suggests that a firm is best viewed as a collection of capabilities that have a composition from and configuration of the tangible and intangible assets of the firm. In this view the firm and its portfolio of capabilities evolve in response to the (perceived) demands of the business environment. An enterprise may comprise one or more firms, or parts of firms (or other types of organization) and their interrelationships – and so is describable (may be modelled) in the same terms.

In the IBM Enterprise Architecture Method, the "Enterprise Capabilities Neighborhood" – a segment of the overall Enterprise Architecture description or model – "captures the strategic intent of the enterprise". It "provides the bridge from the organization's strategy to the architectural building blocks that enable and realize the strategy."[8] According to the IBM EA Method, "Both the Enterprise Capabilities and Business Architecture are technology independent." It is not clear how this view can be rationalised and made coherent with the Leonard model or the Teece theory which places some technology-implemented system at the center of a capability. Collins and De Meo go on to assert that "To focus the EA (description) on delivering the right plan for the enterprise, it must be based on a detailed understanding of the Enterprise Capabilities the enterprise has decided it needs...". Collins and De Meo's "Enterprise Capabilities" can thus be identified with Leonard's "Core Capabilities". The IBM EA Method defines the "Strategic Capability Network" (SCN) which "depicts the strategic capabilities and associated enablers of a business, their interrelationships and their combined roles and significance in ... the value net of a business." The Strategic Capability Network is therefore a modeling technique and network analysis method that expresses both the Leonard model of Core, Enabling and Supplemental capabilities, the Hamel and Prahalad notion of core competencies and, given EA's time dimension of enterprise evolution, the Dynamic Capabilities Theory.

Capability management topics

Capability vs. process

A process is how the capability is executed. Much of the reengineering revolution or Business process reengineering focused on how to redesign business processes.

Business vs. organizational capability

An organization capability refers to the potential of the people in an organization and their cooperation to get things done.[9] The way leaders foster shared mindset, talent, change, accountability, and collaboration across boundaries define the company's culture and leadership edge.

Capability vs. competency

Dave Ulrich makes a distinction between capabilities and competencies: individuals have competencies while organizations have capabilities. Both competencies and capabilities have technical and social elements.

| Individual | Organization | |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | Functional Competencies | Business Capabilities |

| Social | Leadership Competencies | Organizational Capabilities |

At the individual-technical intersection, employees in the firm bring functional skills and competencies such as programming, cost accounting, electrical engineering, etc. At the individual-social intersection, leaders also have a set of competencies or skills such as setting the strategic agenda and building relationships. Moving to the intersection of organizational and technical, are business capabilities. In short, they are the technical things or what the firm must know how to do to execute strategy. For example, a financial service firm must know how to manage risk and design innovative products. Finally, we have organization capabilities such as talent management, collaboration, and accountability. They integrate all the other parts of the firm and bring it together. When leaders have mastered certain competencies, organization capabilities become visible. For example, when leaders master "turning vision in to action" and "aligning the organization," the organization as a whole shows more accountability.

History of capability modeling in business

Capability management's earlier ancestors include the value chain, also known as value chain analysis, first described and popularized by Michael Porter.[10] Core competencies (also called core capabilities) are what give a company one or more competitive advantages in creating and delivering value to its customers in its chosen field, a cluster of extraordinary abilities or the excellence that a firm acquires from its founders, and which cannot be easily imitated.

Lee Perry, Randall Stott and Norm Smallwood[11] added to the capabilities body of work the concepts of strategic options based on customer value proposition and business focus[12] and types of work which characterized work as either:

- Unit of competitive advantage (UCA) – the work and capabilities that create distinctiveness for the business in the marketplace

- Value-added support work – the work and capabilities that facilitate the UCA

- Essential support work – the work that doesn't support UCA or facilitate it but must be done to operate the business

Building on earlier themes, the concept of dynamic capabilities was introduced in 2000. The basic assumption of the dynamic capabilities framework is that in fast changing markets, firms need to respond quickly and innovatively.

Around the same time, Richard Lynch, John Diezemann and James Dowling extended the concepts above in The Capable Company: Building the capabilities that make strategy work.[13] Key additions to the body of work were tools to translate strategic shifts to new sets of capabilities required whether these were core competencies or not. Building on the types of work ideas, the authors added performance target setting based on the capability value contribution. When compared to actual performance, the method outlined an approach to identify capability gaps and priorities. They also laid out a framework to continually align capabilities based on strategy shifts and external changes through the project agenda. The first full capability model was built by the authors in 2001 as the framework for the demerger of Intercontinental Hotels Group (then known as Six Continents) from the parent company Six Continents PLC (formerly Bass & Co Brewery).[14] The model included three levels of capabilities, value contribution, performance targets, capability gaps, recommended actions and sourcing decisions.

In 2004, the UK Ministry of Defence released its enterprise architecture framework, MODAF. This framework extended the existing DoDAF specification by adding views for capability planning. These views were standard ways to represent how the enterprise was expected to perform over time, expressed in terms of capabilities.

Other important contributions include the concept of value maps for detailing the customer proposition and more recently the profit proposition to identify capabilities that will help create Blue Ocean Strategy. Value maps extend the work of real-time strategy and the capable company by depicting a strategy canvas and providing an action framework to capture markets. In the mid-2000s, a team at Microsoft, in concert with Accelare, developed the motion methodology – a capability-based framework.[15] In 2008, Ric Merrifield, Jack Calhoun and Dennis Stevens, in "The Next Revolution in Productivity" added the use of SOA and its role in supporting capability delivery at breakthrough cost and speed.[16] Also introduced was the use of heat maps for capability analyses.

Capability management frameworks

A complete picture of the capabilities is the enterprise capability model.[17] It is a blueprint for the business expressed in terms of the capabilities necessary to execute strategy including delivery of services. Capabilities are described in levels of abstraction; usually three levels of details:

- Family of capabilities; often shown as chevrons[clarification needed]

- Groups of capabilities; illustrated in the health care provider diagram[clarification needed]

- Specific capabilities; the level of detail to assess capabilities

At the higher level, are the attributes of ownership, location, and project road maps. The lower level is where the action is and where performance targets are set, performance assessed and gaps noted. It is at this level sourcing decisions are made or projects established to close gaps. The framework includes strategic, core and enabling capabilities.

- Strategic capabilities: capabilities in organizational planning, strategy, and investment

- Core capabilities: the inventory of business capabilities that are identified as delivering the products and services that an organization offers to its market.

- Enabling capabilities: the inventory of business capabilities that are required to support them but not sold or offered to the market

Strategic planning

Companies like Harvard Pilgrim Health Care[18] and Intercontinental Hotels Group[19] have used capabilities to focus on where to take out costs and outsource non strategic capabilities while improving service and adding brands.

IT–business alignment

Microsoft is using capability models to enter into conversations with clients to identify capability and process pain points to better align IT solutions to the business.[1]

New growth platforms

Capabilities are also being used in new growth platform development.[20] Platforms are a foundation that spawns multiple products and/or services that, by themselves, are eventually the size of a business unit.[21] These innovations result from identifying new domains created at the intersection of enablers or "unstoppable trends" and customer dynamics, linked to an essential set of core capabilities called the platform logic: those capabilities that are unique, valuable, and portable.

Capability value contribution

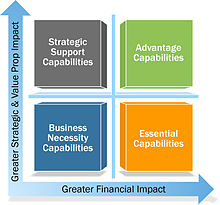

Building of the earlier type of work logic, Accelare added a distinction in assessment of the capabilities necessary to the operative business by examining the financial impact as well as the customer impact.[22]

Some capabilities directly contribute to the customer value proposition and have a high impact on company financials. These "advantage capabilities" are shown in the upper right. Value contribution is assured when performance is among the best in peer organizations at acceptable cost. Keep them inside and protect the intellectual property. Moving to the top left quadrant, strategic support capabilities have high contribution in direct support of advantage capabilities. Keep them close. Value contribution is assured when performed above industry parity at competitive cost. Other capabilities shown in the bottom right are essential. They may not be visible to the customer but contribute to company's business focus and have a big impact on the bottom line. Focus on efficiency improvement; especially in high volume work. Value contribution is assured when performed at industry parity performance below competitors' cost. Other capabilities are "business necessity". Value contribution is assured when performed at industry parity performance below competitors' costs. They can be candidates for alternate sourcing.

Gap analysis and heat maps

A capability gap assessment can be portrayed in a heat map:

- A heat map is a visualization of which capabilities require attention.

- A heat index is calculated using effectiveness and efficiency scores and the gap between targeted and actual performance; high heat (red/orange) in the gap column suggests investment.

Capability value contribution helps stack rank investments, for example advantage capabilities with high heat move to the top of the agenda, followed by business essential capabilities with large inefficiencies.

Variants and alternatives

- Value chain

- Strategy maps

- The MODAF StV-1 Provides a standard way to represent capability planning over time for an enterprise

- The DODAF Capability Viewpoint (CV-) provides a framework to use capabilities in Systems of Systems (SoS) context [23]

- The Coherence Premium is a well streamlined, pragmatic, strategic transformation framework originally from Booz&Co, now acquired by PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PWC), and run under brand 'Strategy&' (Strategy_And).[24]

- The UK Acquisition Organisation Framework AOF, is built around Capability Management backbone.[25]

- A pragmatic tool-supported implementation of the AoF framework (from SVGC Ltd) is combining Capability Management with materials and logistics management [26]

- IT-CMF – is a comprehensive capability management framework for IT enabled businesses.[27]

- A pragmatic tool-supported implementation of the IT-CMF framework (from Mitovia Inc) is combining Capability Management with roadmapping, asset management and decision support. Solution is well suited for supporting capability driven transformation programs. People behind Mitovia are also contributing members for IT-CMF.[28]

See also

- Capability management in defense

- Capability approach in welfare economics

- Relationship to operating model

- Relationship to enterprise architecture

- Relationship to business architecture

References

- ^ Edith Penrose (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. New York, John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-19-828977-7.

- ^ Leonard, 1998

- ^ Leonard, Dorothy (1995). Wellsprings of Knowledge. Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 978-0-87584-612-5.

- ^ Ric Merrifield, Jack Calhoun and Dennis Stevens "The Next Revolution in Productivity", (Harvard Business Review, June, 2008)

- ^ a b c Hadaya, Pierre; Gagnon, Bernard (2017). Business architecture : the missing link in strategy formulation, implementation and execution. Montréal: ASATE Publishing. pp. 59–60. ISBN 9780994931900. OCLC 989865288.

- ^ Teece, D., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). "Dymamic Capabilities and Strategic Management". Strategic Management Journal. 18 (7): 509–533. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.390.9899. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::aid-smj882>3.0.co;2-z. S2CID 167484845.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Capability-Based Planning Paradigm". The Open Group. 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Collins, F.C.; De Meo, P. (2011). "Realizing the Business Value of Enterprise Architecture through Architecture Building Blocks". In Doucet, G.; Gotze, J.; Saha, P.; Bernard, S. (eds.). Coherency Management – Architecting the Enterprise for Alignment, Agility and Assurance. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4389-9606-6.

- ^ Dave Ulrich and Norn Smallwood, How Leaders Build Value: Using People, Organization, and Other Intangibles to Get Bottom-Line Results (Jossey-Bass, 2006)

- ^ Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. 1985.

- ^ Lee Perry, Randall Stott and Norm Smallwood Real Time Strategy (Wiley 1993)

- ^ Benjamin B. Tregoe and John W. Zimmerman Top Management Strategy (Simon & Schuster, 1980) Business Focus builds on the work of the "driving force" and "nine strategic areas" and how they suggest capabilities needed.

- ^ Richard Lynch, John Diezemann and James Dowling, The Capable Company: Building the capabilities that make strategy work (Wiley-Blackwell, 2003)

- ^ James Larson and Richard Lynch, "Reinventing a Hotel Company" (BPM Connections, October/November 2004)

- ^ Ric Merrifield, Rethink: What do you need to do today? (FT Press, 2009)

- ^ Ric Merrifield, Jack Calhoun and Dennis Stevens "The Next Revolution in Productivity", (Harvard Business Review, June 2008)

- ^ Capability-Based Management (White Paper from Accelare, 2009)

- ^ Jack Calhoun, Richard Lynch and Jim Dowling, "The Cost-Take-Out Challenge", (www.accelare.com).

- ^ James Larson and Richard Lynch, "Reinventing a Hotel Company"(October/November 2004 issue of BPM Connections)

- ^ Donald L. Laurie, Claude Sheer and Yves Doz, "New Growth Platforms" (Harvard Business Review, May 2006)

- ^ Leander Kahney, "Straight Dope on the IPod's Birth" (Wired, October 17, 2006) illustrates this concept well.

- ^ Jack Calhoun, Richard Lynch and Jim Dowling, The Cost-Take-Out Challenge, (Accelare, 2009).

- ^ "DODAF Viewpoints and Models - Capability Viewpoint".

- ^ "The Coherence Premium".

- ^ "Defence Gateway - Login". Archived from the original on 2022-11-06. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ http://svgc.co.uk/

- ^ "IT-CMF".

- ^ "The Value Management Platform – Mitovia Inc".