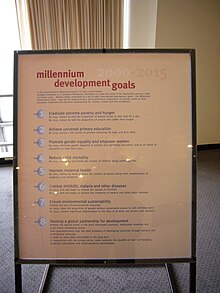

A high-level statement of intent or direction for an organization. Typically used to measure the success of an organization.

| Part of a series on |

| Agency |

|---|

| In different fields |

| Theories |

| Processes |

| Individual difference |

| Concepts |

| Self |

| Free will |

A goal or objective is an idea of the future or desired result that a person or a group of people envision, plan, and commit to achieve.[1] People endeavour to reach goals within a finite time by setting deadlines.

A goal is roughly similar to a purpose or aim, the anticipated result which guides reaction, or an end, which is an object, either a physical object or an abstract object, that has intrinsic value.

Goal setting

Goal-setting theory was formulated based on empirical research and has been called one of the most important theories in organizational psychology.[2] Edwin A. Locke and Gary P. Latham, the fathers of goal-setting theory, provided a comprehensive review of the core findings of the theory in 2002.[3] In summary, Locke and Latham found that specific, difficult goals lead to higher performance than either easy goals or instructions to "do your best", as long as feedback about progress is provided, the person is committed to the goal, and the person has the ability and knowledge to perform the task.

According to Locke and Latham, goals affect performance in the following ways:[3]

- goals direct attention and effort toward goal-relevant activities,

- difficult goals lead to greater effort,

- goals increase persistence, with difficult goals prolonging effort, and

- goals indirectly lead to arousal, and to discovery and use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies

Some coaches recommend establishing specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bounded (SMART) objectives, but not all researchers agree that these SMART criteria are necessary.[4] The SMART framework does not include goal difficulty as a criterion; in the goal-setting theory of Locke and Latham, it is recommended to choose goals within the 90th percentile of difficulty, based on the average prior performance of those that have performed the task.[5][3]

Goals can be long-term, intermediate, or short-term. The primary difference is the time required to achieve them.[6] Short-term goals are expect to be finished in a relatively short period of time, long-term goals in a long period of time, and intermediate in a medium period of time.

Mindset theory of action phases

Before an individual can set out to achieve a goal, they must first decide on what their desired end-state will be. Peter Gollwitzer's mindset theory of action phases proposes that there are two phases in which an individual must go through if they wish to achieve a goal.[7] For the first phase, the individual will mentally select their goal by specifying the criteria and deciding on which goal they will set based on their commitment to seeing it through. The second phase is the planning phase, in which the individual will decide which set of behaviors are at their disposal and will allow them to best reach their desired end-state or goal.[8]: 342–348

Goal characteristics

Certain characteristics of a goal help define the goal and determine an individual's motivation to achieve that goal. The characteristics of a goal make it possible to determine what motivates people to achieve a goal, and, along with other personal characteristics, may predict goal achievement.[citation needed]

- Importance is determined by a goal's attractiveness, intensity, relevance, priority, and sign.[8][page needed] Importance can range from high to low.

- Difficulty is determined by general estimates of probability of achieving the goal.[8][page needed]

- Specificity is determined if the goal is qualitative and ranges from being vague to precisely stated.[8][page needed] Typically, a higher-level goal is vaguer than a lower level subgoal; for example, wanting to have a successful career is vaguer than wanting to obtain a master's degree.

- Temporal range is determined by the duration of the goal and the range from proximal (immediate) to distal (delayed).[8][page needed]

- Level of consciousness refers to a person's cognitive awareness of a goal. Awareness is typically greater for proximal goals than for distal goals.[8][page needed]

- Complexity of a goal is determined by how many subgoals are necessary to achieve the goal and how one goal connects to another.[8][page needed] For example, graduating college could be considered a complex goal because it has many subgoals (such as making good grades), and is connected to other goals, such as gaining meaningful employment.

Personal goals

Individuals can set personal goals: a student may set a goal of a high mark in an exam; an athlete might run five miles a day; a traveler might try to reach a destination city within three hours; an individual might try to reach financial goals such as saving for retirement or saving for a purchase.

Managing goals can give returns in all areas of personal life. Knowing precisely what one wants to achieve makes clear what to concentrate and improve on, and often can help one subconsciously prioritize on that goal. However, successful goal adjustment (goal disengagement and goal re-engagement capacities) is also a part of leading a healthy life.[9]

Goal setting and planning ("goal work") promotes long-term vision, intermediate mission and short-term motivation. It focuses intention, desire, acquisition of knowledge, and helps to organize resources.

Efficient goal work includes recognizing and resolving all guilt, inner conflict or limiting belief that might cause one to sabotage one's efforts. By setting clearly-defined goals, one can subsequently measure and take pride in the accomplishment of those goals. One can see progress in what might have seemed a long, perhaps difficult, grind.

Achieving personal goals

Achieving complex and difficult goals requires focus, long-term diligence, and effort (see Goal pursuit). Success in any field requires forgoing excuses and justifications for poor performance or lack of adequate planning; in short, success requires emotional maturity. The measure of belief that people have in their ability to achieve a personal goal also affects that achievement.

Long-term achievements rely on short-term achievements. Emotional control over the small moments of the single day can make a big difference in the long term.

Personal goal achievement and happiness

There has been a lot of research conducted looking at the link between achieving desired goals, changes to self-efficacy and integrity and ultimately changes to subjective well-being.[10] Goal efficacy refers to how likely an individual is to succeed in achieving their goal. Goal integrity refers to how consistent one's goals are with core aspects of the self. Research has shown that a focus on goal efficacy is associated with happiness, a factor of well-being, and goal integrity is associated with meaning (psychology), another factor of well-being.[11] Multiple studies have shown the link between achieving long-term goals and changes in subjective well-being; most research shows that achieving goals that hold personal meaning to an individual increases feelings of subjective well-being.[12][13][14]

Psychologist Robert Emmons found that when humans pursue meaningful projects and activities without primarily focusing on happiness, happiness often results as a by-product. Indicators of meaningfulness predict positive effects on life, while lack of meaning predicts negative states such as psychological distress. Emmons summarizes the four categories of meaning which have appeared throughout various studies. He proposes to call them WIST, or work, intimacy, spirituality, and transcendence.[15] Furthermore, those who value extrinstic goals higher than intrinsic goals tend to have lower subjective well-being and higher levels of anxiety.[16]

Self-concordance model

The self-concordance model is a model that looks at the sequence of steps that occur from the commencement of a goal to attaining that goal.[17] It looks at the likelihood and impact of goal achievement based on the type of goal and meaning of the goal to the individual.[citation needed] Different types of goals impact both goal achievement and the sense of subjective well-being brought about by achieving the goal. The model breaks down factors that promote, first, striving to achieve a goal, then achieving a goal, and then the factors that connect goal achievement to changes in subjective well-being.

Self-concordant goals

Goals that are pursued to fulfill intrinsic values or to support an individual's self-concept are called self-concordant goals. Self-concordant goals fulfill basic needs and align with what psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott called an individual's "True Self". Because these goals have personal meaning to an individual and reflect an individual's self-identity, self-concordant goals are more likely to receive sustained effort over time. In contrast, goals that do not reflect an individual's internal drive and are pursued due to external factors (e.g. social pressures) emerge from a non-integrated region of a person, and are therefore more likely to be abandoned when obstacles occur.[18]

Those who attain self-concordant goals reap greater well-being benefits from their attainment. Attainment-to-well-being effects are mediated by need satisfaction, i.e., daily activity-based experiences of autonomy, competence, and relatedness that accumulate during the period of striving. The model is shown to provide a satisfactory fit to 3 longitudinal data sets and to be independent of the effects of self-efficacy, implementation intentions, avoidance framing, and life skills.[19]

Furthermore, self-determination theory and research surrounding this theory shows that if an individual effectively achieves a goal, but that goal is not self-endorsed or self-concordant, well-being levels do not change despite goal attainment.[20]

Goal setting management in organizations

In organizations, goal management consists of the process of recognizing or inferring goals of individual team-members, abandoning goals that are no longer relevant, identifying and resolving conflicts among goals, and prioritizing goals consistently for optimal team-collaboration and effective operations.

For any successful commercial system, it means deriving profits by making the best quality of goods or the best quality of services available to end-users (customers) at the best possible cost.[citation needed] Goal management includes:

- assessment and dissolution of non-rational blocks to success

- time management

- frequent reconsideration (consistency checks)

- feasibility checks

- adjusting milestones and main-goal targets

Jens Rasmussen and Morten Lind distinguish three fundamental categories of goals related to technological system management. These are:[21]

Organizational goal-management aims for individual employee goals and objectives to align with the vision and strategic goals of the entire organization. Goal-management provides organizations with a mechanism[which?] to effectively communicate corporate goals and strategic objectives to each person across the entire organization.[citation needed] The key consists of having it all emanate from a pivotal source and providing each person with a clear, consistent organizational-goal message, so that every employee understands how their efforts contribute to an enterprise's success.[citation needed]

An example of goal types in business management:

- Consumer goals: this refers to supplying a product or service that the market/consumer wants[22]

- Product goals: this refers to supplying an outstanding value proposition compared to other products - perhaps due to factors such as quality, design, reliability and novelty[23]

- Operational goals: this refers to running the organization in such a way as to make the best use of management skills, technology and resources

- Secondary goals: this refers to goals which an organization does not regard as priorities[citation needed]

Goal displacement

Goal displacement occurs when the original goals of an entity or organization are replaced over time by different goals. In some instances, this creates problems, because the new goals may exceed the capacity of the mechanisms put in place to meet the original goals. New goals adopted by an organization may also increasingly become focused on internal concerns, such as establishing and enforcing structures for reducing common employee disputes.[24] In some cases, the original goals of the organization become displaced in part by repeating behaviors that become traditional within the organization. For example, a company that manufactures widgets may decide to do seek good publicity by putting on a fundraising drive for a popular charity or by having a tent at a local county fair. If the fundraising drive or county fair tent is successful, the company may choose to make this an annual tradition, and may eventually involve more and more employees and resources in the new goal of raising the most charitable funds or of having the best county fair tent. In some cases, goals are displaced because the initial problem is resolved or the initial goal becomes impossible to pursue. A famous example is the March of Dimes, which began as an organization to fund the fight against polio, but once that disease was effectively brought under control by the polio vaccine, transitioned to being an organization for combating birth defects.[24]

See also

- Counterplanning

- Decision-making software

- Direction of fit

- GOAL agent programming language

- Goal modeling

- Goal orientation

- Goal programming

- Goal–question–metric (GQM)

- Goal theory

- Management by objectives

- Moving the goalposts

- Objectives and key results (OKR)

- Polytely

- Regulatory focus theory

- Strategic management

- Strategic planning

- SWOT analysis

- The Goal (novel)

- The Jackrabbit Factor

References

- ^ Locke, Edwin A.; Latham, Gary P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0139131387. OCLC 20219875.

- ^ Miner, J. B. (2003). "The rated importance, scientific validity, and practical usefulness of organizational behavior theories: A quantitative review". Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2 (3): 250–268. doi:10.5465/amle.2003.10932132.

- ^ a b c Locke, Edwin A.; Latham, Gary P. (September 2002) [2002]. "Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey". American Psychologist. 57 (9): 705–717. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.126.9922. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705. PMID 12237980. S2CID 17534210.

- ^ Grant, Anthony M (September 2012). "An integrated model of goal-focused coaching: an evidence-based framework for teaching and practice" (PDF). International Coaching Psychology Review. 7 (2): 146–165 (147). doi:10.53841/bpsicpr.2012.7.2.146. S2CID 255938190. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-29.

Whilst the ideas represented by the acronym SMART are indeed broadly supported by goal theory (e.g. Locke, 1996), and the acronym SMART may well be useful in some instances in coaching practice, I think that the widespread belief that goals are synonymous with SMART action plans has done much to stifle the development of a more sophisticated understanding and use of goal theory within in the coaching community, and this point has important implications for coaching research, teaching and practice.

- ^ Locke, E. A., Chah, D., Harrison, S. & Lustgarten, N. (1989). "Separating the effects of goal specificity from goal level". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 43 (2): 270–287. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(89)90053-8.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Creek, Jennifer; Lougher, Lesley (2008). "Goal setting". Occupational therapy and mental health (4th ed.). Edinburgh; New York: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. pp. 111–113 (112). ISBN 9780443100277. OCLC 191890638.

Client goals are usually set on two or three levels. Long-term goals are the overall goals of the intervention, the reasons why the client is being offered help, and the expected outcome of intervention... Intermediate goals may be clusters of skills to be developed, attitudes to be changed or barriers to be overcome on the way to achieving the main goals... Short-term goals are the small steps on the way to achieving major goals.

- ^ Gollwitzer, P. M. (2012). Mindset theory of action phases. In P. A. M. Van Lange. A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Handbook of motivation science (pp. 235–250). New York: Guilford Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Deckers, Lambert (2018). Motivation: biological, psychological, and environmental (5th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138036321. OCLC 1009183545.

- ^ Wrosch, Carsten; Scheier, Michael F.; Miller, Gregory E. (2013-12-01). "Goal Adjustment Capacities, Subjective Well-Being, and Physical Health". Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 7 (12): 847–860. doi:10.1111/spc3.12074. ISSN 1751-9004. PMC 4145404. PMID 25177358.

- ^ Emmons, Robert A (1996). "Striving and feeling: personal goals and subjective well-being". In Gollwitzer, Peter M; Bargh, John A (eds.). The psychology of action: linking cognition and motivation to behavior. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 313–337. ISBN 978-1572300323. OCLC 33103979.

- ^ McGregor, Ian; Little, Brian R (February 1998). "Personal projects, happiness, and meaning: on doing well and being yourself". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (2): 494–512. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.494. PMID 9491589.

- ^ Brunstein, Joachim C (November 1993). "Personal goals and subjective well-being: a longitudinal study". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 65 (5): 1061–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.1061.

- ^ Elliott, Andrew J; Sheldon, Kennon M (November 1998). "Avoidance personal goals and the personality–illness relationship". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (5): 1282–1299. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.433.3924. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.5.1282. PMID 9866188.

- ^ Sheldon, Kennon M; Kasser, Tim (December 1998). "Pursuing personal goals: skills enable progress but not all progress is beneficial" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 24 (12): 1319–1331. doi:10.1177/01461672982412006. S2CID 143050092. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-13. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- ^ Emmons, Robert A. (2003), Keyes, Corey L. M.; Haidt, Jonathan (eds.), "Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life.", Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived., Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 105–128, doi:10.1037/10594-005, ISBN 978-1-55798-930-7, retrieved 2023-11-07

- ^ Kasser, Tim; Ryan, Richard M. (March 1996). "Further Examining the American Dream: Differential Correlates of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goals". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 22 (3): 280–287. doi:10.1177/0146167296223006. ISSN 0146-1672. S2CID 143559692.

- ^ Sheldon, Ken M; Eliott, Andrew J (March 1999). "Goal striving, need satisfaction and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (3): 482–497. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482. PMID 10101878.

- ^ Gollwitzer, Peter M (1990). "Action phases and mind-sets" (PDF). In Higgins, E Tory; Sorrentino, Richard M (eds.). Handbook of motivation and cognition: foundations of social behavior. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 53–92. ISBN 978-0898624328. OCLC 12837968.

- ^ Sheldon, Kennon M; Elliot, Andrew J (March 1999). "Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (3): 482–497. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482. PMID 10101878.

- ^ Ryan, Richard M (January 2000). "Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being" (PDF). American Psychologist. 55 (1): 68–78. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.529.4370. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68. PMID 11392867. S2CID 1887672.

- ^ Rasmussen, Jens; Lind, Morten (1982). "A model of human decision making in complex systems and its use for design of system control strategies" (PDF). Proceedings of the 1982 American Control Conference: Sheraton National Hotel, Arlington, Virginia, June 14–16, 1982. New York: American Automatic Control Council. OCLC 761373599. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2015-02-06. Cited in: Wrench, Jason S (2013). "Communicating within the modern workplace: challenges and prospects". In Wrench, Jason S (ed.). Workplace communication for the 21st century: tools and strategies that impact the bottom line. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-0313396311. OCLC 773022358.

- ^ Osterwalder, Alexander; Pigneur, Yves; Clark, Tim (2010). Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470876411. OCLC 648031756.

- ^ Barnes, Cindy; Blake, Helen; Pinder, David (2009). Creating & delivering your value proposition: managing customer experience for profit. London; Philadelphia: Kogan Page. ISBN 9780749455125. OCLC 320800660.

- ^ a b Karen Kirst-Ashman, Human Behavior, Communities, Organizations, and Groups in the Macro Social Environment (2007), p. 112.

Further reading

- Mager, Robert Frank (1997) [1972]. Goal analysis: how to clarify your goals so you can actually achieve them (3rd ed.). Atlanta, GA: Center for Effective Performance. ISBN 978-1879618046. OCLC 37435274.

- Moskowitz, Gordon B; Heidi Grant Halvorson, eds. (2009). The psychology of goals. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 9781606230299. OCLC 234434698.